Function Identification in ESP32 Firmware Using Ghidra FIDB

Reverse engineering firmware on ESP32 devices is slowed down by the absence of debugging symbols, forcing the manual identification of functions. This article explains how to use Ghidra’s Function Identification Databases (FIDB) together with ESP-IDF to automate function identification and transform an opaque binary into understandable code in a matter of minutes.

An important part of vulnerability analysis projects on hardware and IoT devices is firmware analysis.

Firmware is generally compiled without debugging symbols due to storage memory size constraints. This makes reverse engineering more difficult because there is no information about the functions in the binary, and they must be identified manually.

The ESP32 microcontroller has gained popularity in embedded devices due to its low cost and integrated WiFi and Bluetooth communications. Firmware analysis for this chip presents the same difficulties resulting from the lack of symbols in firmware binaries. Espressif, the manufacturer of the ESP32, provides an SDK to program the ESP32 family of chips, ESP-IDF. This development framework consists of all the components necessary to create a firmware project that runs on ESP32 chips, from low-level peripheral drivers to advanced libraries.

The use of a single SDK for most projects based on this family of microcontrollers means that firmware shares a large amount of code. This is where Ghidra’s Function Identification Databases (FIDB) functionality comes into play, allowing us to generate databases with metadata from ESP-IDF functions and automatically identify them in stripped binaries. This speeds up the firmware reverse engineering process, since thanks to FIDB it is not necessary to manually identify SDK functions.

Ghidra Function ID Databases (FIDB)

Function Identification Databases (FIDB) are indexed databases that allow Ghidra to automatically identify functions from known libraries within compiled binaries by comparing hashes. When a program is statically compiled with libraries, functions lose their original names and remain as anonymous blocks of machine code. FIDB solves this problem by storing precomputed hashes of known functions along with their metadata (name, library version, compilation variant), making it possible to recover the original identification.

The process consists of two parts:

- FIDB Database Generation: All functions in one or more binaries whose functions are labeled with names—that is, in binaries with symbols—are processed. For each function, two hashes are generated and stored in the database along with its name and other metadata.

- Function identification with FIDB: During the function identification process in a stripped binary, each function in the binary is analyzed, generating the two hashes for each one. The generated hashes are compared with those stored in the previously created FIDB database, and if a match is found, the function’s metadata from the database is used to label the function in the analyzed binary.

For each function, two hashes are calculated:

- Full hash: Includes the mnemonics (the names of assembly instructions, e.g., MOV, ADD, JMP) and addressing information, but ignores specific constant values, making it resilient to relocations during linking.

- Specific hash: Includes all elements in the full hash and additionally incorporates constant operand values, as long as these constants are not related to addressing.

To resolve matches or ambiguities, the system examines the function’s call tree. If two functions are identical but call different subfunctions, the hashes of those subfunctions allow them to be distinguished.

The analyzer calculates scores based on matching instructions, also summing the scores of matching parent and child functions. FIDB allows configurable thresholds to be applied to these scores to filter out random matches in small functions, reporting the name when candidates can be reduced to a single option, or multiple possibilities when ambiguity persists.

Identifying the ESP-IDF Version

It is possible that the firmware we are going to analyze was compiled with an older version of ESP-IDF. Updates introduce changes in the code and API; therefore, to generate a Ghidra Function Identification Database (FIDB) that identifies the maximum number of functions in the device firmware, it must be done using the correct version of ESP-IDF.

There are different methods to identify the IDF version used in the firmware being analyzed.

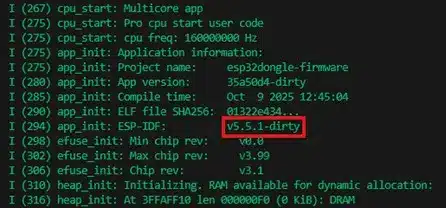

First, we can check the device logs via the serial port. ESP32 chips implement a UART interface through which the bootloader exposes an interface that allows, among other things, reading and writing firmware from flash memory. By default, the firmware writes debugging information to this interface, including messages from both ESP-IDF and the application itself. During ESP-IDF initialization, the version number is written to the UART interface.

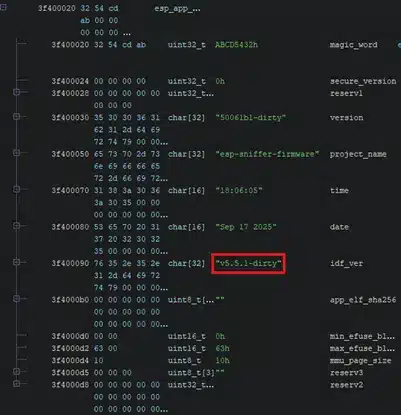

However, it is very common for debugging logs to be disabled on production devices. In this case, the user code section in the firmware binary includes a header that contains the ESP-IDF version number.

Once the version number is obtained, that version is installed and the ESP-IDF code for that version is compiled. Each version has its own compilation toolchain, which is an advantage for function identification using FIDB, since by default ESP-IDF fixes a specific compiler for all builds, ensuring that the machine code generated for a piece of code will be the same across all devices using that ESP-IDF version.

During the ESP-IDF installation, it is important to set the IDF version by using the corresponding GitHub repository tag when installing the SDK.

mkdir -p ~/esp cd ~/esp git clone -b v5.5.1 --recursive https://github.com/espressif/esp-idf.git cd ~/esp/esp-idf ./install.sh

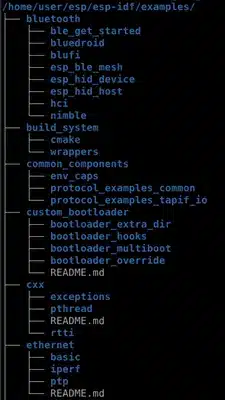

Once the ESP-IDF version matching the device being analyzed is installed, the ESP-IDF code is compiled using the various example projects distributed with the IDF SDK, which are located in the examples directory.

A good approach to generate a FIDB with the maximum number of ESP-IDF functions is to compile all the example projects to create a database covering most of the ESP-IDF components, which can then be reused in future projects. If a component is not used in any of the ESP-IDF example projects, it is necessary to create a project that includes calls to those components so they are included in the binary.

To compile an example project, the project directory from the IDF is copied to the build directory, and the tool provided by IDF is executed:

idf build

Creating the Ghidra project

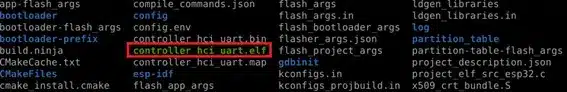

Once the project is compiled, an executable in ELF format is generated in the build directory. This ELF file contains the symbols which, once extracted, allow Ghidra to identify all the functions in the code and generate a FIDB with them.

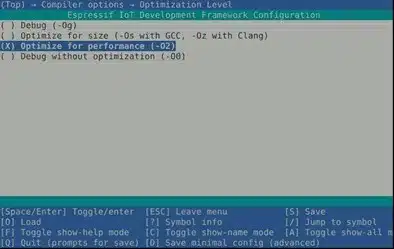

Projects can be compiled with different optimizations, and the IDF configuration allows compiling with size optimization (-Os) or performance optimization (-O2). It is recommended to generate the binaries for each project with both optimizations, as each can produce different machine code, and we may not know which optimization was used for the firmware being analyzed, thus maximizing the chances of later identifying the functions.

The compiler optimization is selected using the ESP-IDF configuration menu:

idf menuconfig

Compiler Options > Optimization Level

Once the compiler optimization is selected, the projects are recompiled with that optimization.

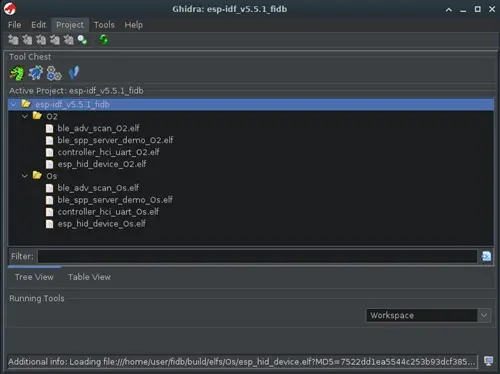

After all the projects containing the functions of interest are compiled, a Ghidra project is created and the ELF-format binaries are imported.

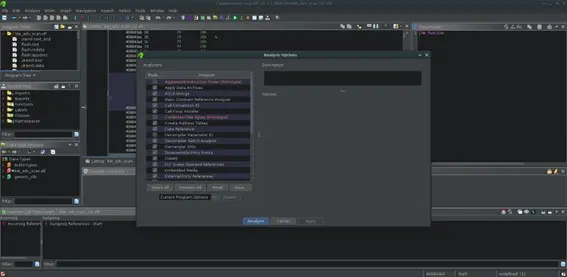

We now have a Ghidra project containing all the example project binaries with various optimizations. It is necessary to run an auto-analysis for each binary from the Code Browser tool. This analysis labels and decompiles all the functions in the binary. Once each program is analyzed, it is saved.

Generating the FIDB database

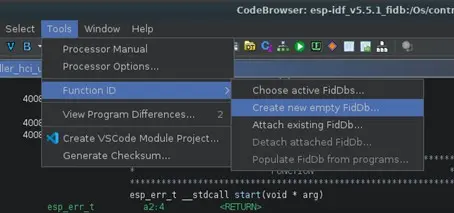

Once all the binaries have been analyzed, we proceed to create the FIDB databases for all of them by opening any of the binaries in the Ghidra project with the Code Browser tool. From there, the FIDB database is created via Tools > Function ID > Create New Empty FIDB…, selecting the path where we want to save the database.

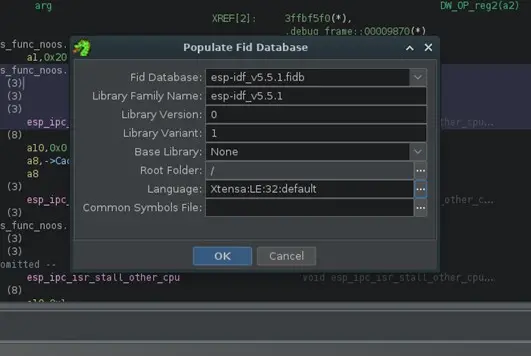

Using the Populate FIDB from Programs… option in the same menu, the FIDB database is created from the project’s programs. It asks for several pieces of information, such as the name, version, root directory of the project to include all project programs, and the “language”, where we select Xtensa:LE:32:default, which is the architecture of the ESP32.

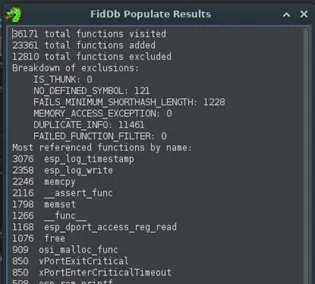

When the FIDB creation is complete, Ghidra displays a report of the functions added to the database. In this example, a total of 23,361 functions were added. It also indicates that 12,810 functions were excluded, the majority of them because they were duplicated across the different binaries in the project.

At this point, we have a .fidb file, which is the generated FIDB database that can be imported into different Ghidra instances for function identification.

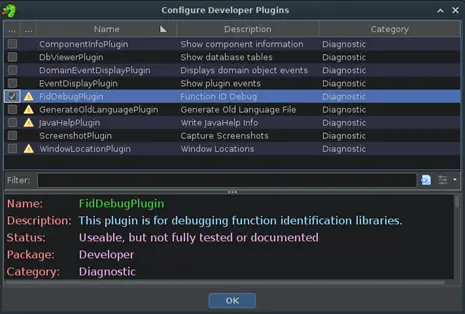

It is possible to explore the contents of the FIDB database by enabling the FIDB debugging plugin. In the Code Browser window, go to File > Configure, and within the Developer section, open the configure menu and activate the FidDebugPlugin option.

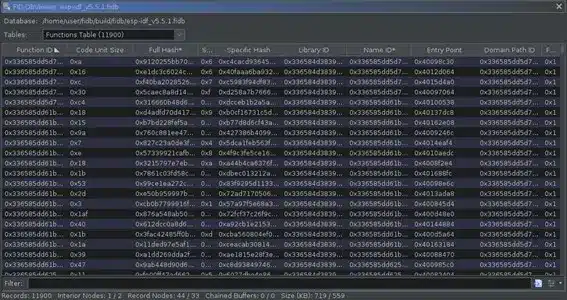

Now, in the Tools > Function ID section, additional options appear, such as Table Viewer, which allows us to navigate through the FIDB database and explore its contents.

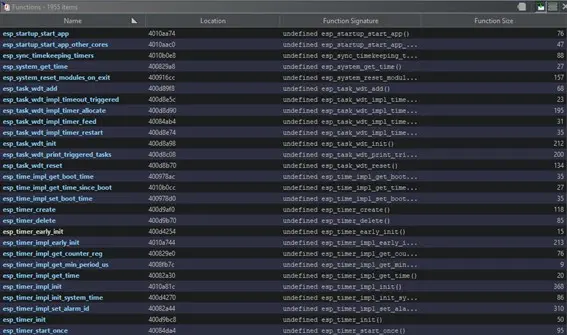

Identifying functions in firmware without symbols

Now that we have the FIDB database, we can use it to identify functions in a firmware binary without symbols.

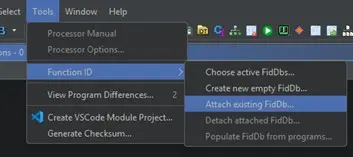

In Ghidra, with the firmware project open, make sure the FIDB database is imported via Tools > Function ID > Attach Existing FIDB….

Next, an analysis pass is performed using the Function ID analyzer. This analyzer generates hashes for the functions in the binary and compares them with those stored in the FIDB database, so that functions with matching hashes are automatically labeled.

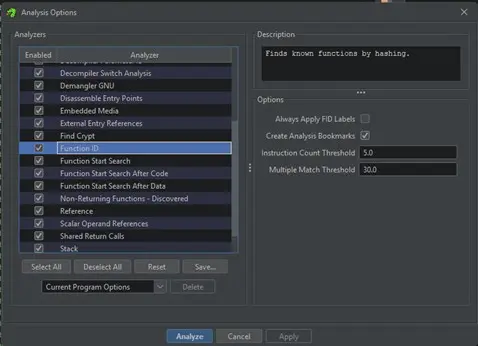

The analyzer is run from the Analysis window via Analysis > Auto Analyze ‘file.bin’…. In the analysis window, select the Function ID analyzer. Various options can be passed to the analyzer:

- Always Apply FID Labels: If the analyzer detects a match with a function, it will assign the name from the FIDB even if the function is already labeled.

- Create Analysis Bookmarks: The analyzer creates bookmarks on the identified functions.

- Instruction Count Threshold: The minimum number of instructions that must match the functions in the FIDB for the analyzer to identify the function. A very low threshold may cause false positives; a very high threshold means only large functions will be identified.

- Multiple Match Threshold: The minimum threshold for reporting multiple matches when a single function name cannot be determined. A high threshold reports fewer multiple matches; a low threshold reports less reliable multiple matches.

With analysis using the FIDB database, a large portion of the ESP-IDF functions are identified.

This simplifies the analysis of the application part of the device firmware, as the framework’s functions have already been identified thanks to FIDB.

In conclusion

Ghidra’s Function Identification Database (FIDB) functionality is a powerful tool for reverse engineering, particularly for code without debugging symbols, such as device firmware.

This article takes advantage of the fact that most ESP32-based devices share the same SDK code base provided by Espressif. This allows a database to be generated once and reused across different reverse engineering projects for this type of chip.

Although creating these databases can be a labor-intensive process, requiring the compilation of multiple projects to cover the entire ESP-IDF, it is easily automated thanks to Ghidra’s headless analysis utility. There are articles exploring the process of importing, analyzing, and creating FIDB databases in an automated way:

https://blog.threatrack.de/2019/09/20/ghidra-fid-generator

In summary, using FIDB in Ghidra for the ESP32 chip family represents a significant shift in how firmware without symbols is analyzed, moving from a manual and repetitive approach to a systematic and reusable one. By investing time once to generate a well-constructed database aligned with the specific ESP-IDF version, future reverse engineering processes are greatly accelerated, errors are reduced, and effort can be focused on analyzing the device-specific logic and potential vulnerabilities rather than identifying common framework code.

References:

- https://htmlpreview.github.io/

- https://github.com/NationalSecurityAgency/ghidra/blob/master/Ghidra/Features/FunctionID/src/main/help/help/topics/FunctionID/FunctionID.html

- https://blog.threatrack.de/2019/09/20/ghidra-fid-generator/

- https://github.com/threatrack/ghidra-fid-generator

- https://docs.espressif.com/projects/esp-idf/en/stable/esp32/get-started/linux-macos-setup.html