Liberating Bluetooth on the ESP32

The ESP32 has become an ubiquitous platform, powering everything from millions of commercial devices to one-off devices built by the hacker and maker communities. While its Wi-Fi stack has been the subject of previous reverse engineering efforts, its Bluetooth subsystem remains largely undocumented and closed source despite being present in millions of devices.

This is a reverse engineering effort to document Espressif’s proprietary Bluetooth stack, with a focus on enabling low-level access for researchers, security analysts, and developers to improve existing affordable and open Bluetooth tooling.

This research was originally carried out as part of our Bluetooth security research line and expands on the notes and findings shared in the 39C3 talk.

As part of the Bluetooth research line carried out in the last years, many publications have followed. Vulnerabilities, such as BlueTrust and BlueSpy, have been found. A big effort towards standardization was accomplished with the publication of BSAM, a creative commons licensed methodology for Bluetooth security assessment.

Currently, despite the organized information, it remains challenging to implement some of the proposals. security checks due to a lack of affordable tools to implement and execute those checks. For this reason, the effort of the research line is now on achieving accessible tooling and resources to follow the existing methodology.

The new challenge is to have access to Bluetooth lower layers in a well-documented and accessible way. Surprisingly, there are few examples of Bluetooth controllers that are open source.

Why the ESP32?

When looking for an affordable Bluetooth device to reverse engineer, one must take into consideration the Espressif ESP32. The price per device and the availability are hard to beat but this is complemented with many other reasons that make it one of the best candidates for open sourcing:

- The device supports both Bluetooth Classic and Low Energy, while many others do not.

- The device SDK is almost fully open source already, having only to reverse engineer the remaining pieces.

- The remaining closed source blobs in the SDK are Apache licensed, which allows derivative work that arises from them to be published!

Collecting ESP32 code

Espressif publishes all their closed source blobs as part of their SDK. Mainly we were interested in the ESP32 ROMs (https://github.com/espressif/esp-rom-elfs/releases), the Bluetooth libraries and the radio frequency peripheral libraries.

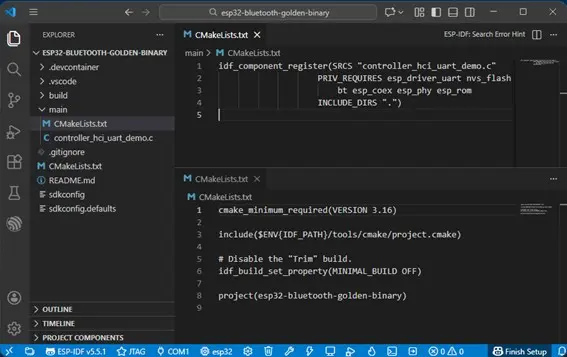

All the above components are published in separated libraries which makes them harder to analyse in Ghidra. Fortunately, we can generate a “golden binary” that combines all of them into a single ELF file. We have documented how to do this in the past using the ESP toolchain using the linker tools. As a simple alternative way to achieve a golden binary, we have created an ESP-IDF standard project that anyone can compile by specifying the libraries we want to reverse engineer as dependencies and by instructing CMake to not «strip» or «trim» the resulting binary, keeping all functions and code even if it is not used! You can find the golden binary project in GitHub.

Figure 1. Golden binary project.

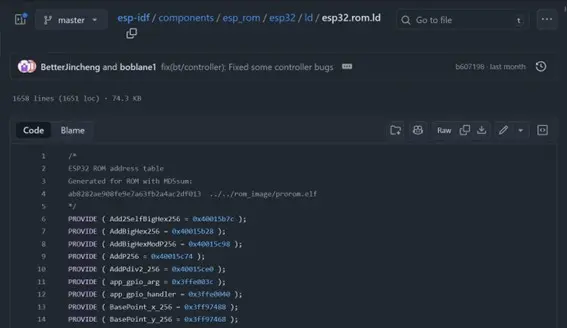

Espressif, in their SDK, also publish linker scripts that allow user applications to compile against their internal ROMs. The linker scripts contain useful information such as function names and addresses that can greatly simplify the feat of understanding the internal code.

Figure 2. Sample linker script file from the ESP32 SDK.

A plugin for Ghidra has been created to be able to import function names and addresses automatically. The plugin is called GhidraLinkerScript and can be found at GitHub.

Now the reverse engineering process is aided by the extra context that function names can provide. This greatly helps understand the purpose of some parts of the internal ESP32 ROM code.

Known peripherals information

Once all the relevant information regarding code has been loaded into Ghidra, we faced a couple of obstacles.

The ELF only contained memory related to the code and some RAM. Unfortunately, the code interacts directly with peripheral memory whose information was not loaded into the Ghidra memory map…

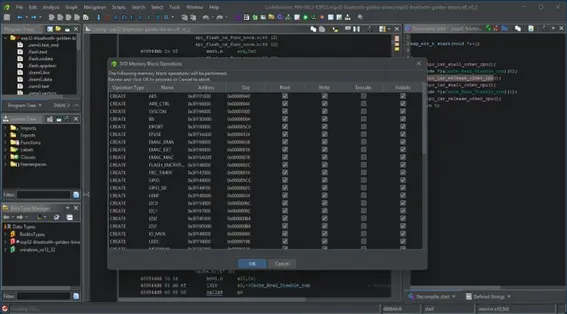

The ESP32 datasheet contains information about these memory regions, but this information is not particularly detailed and is also tedious to incorporate by hand. Fortunately, this information is also available in a parseable format called SVD! SVD is an XML-based standard that was originally conceived for ARM but has become widely used to document chip information so that other tools can generate code or facilitate debugging tasks.

Espressif publishes their own SVD files at Github but those are quite outdated. The Espressif Rust community handles a repository that patches those outdated SVD files to produce more up to date versions (link here).

Ghidra does not natively support importing SVD information but a plugin for this has been developed and can be found here.

Figure 3. Ghidra SVD information import process.

After importing the SVD information, Ghidra will be able to correctly display the name of memory regions that were previously unknown, at least for the already document ones in the SVD file.

The missing bits

Now that all the available information is loaded into Ghidra, we would like to document the missing memory regions, particularly, those regions that may be heavily used in Bluetooth related code.

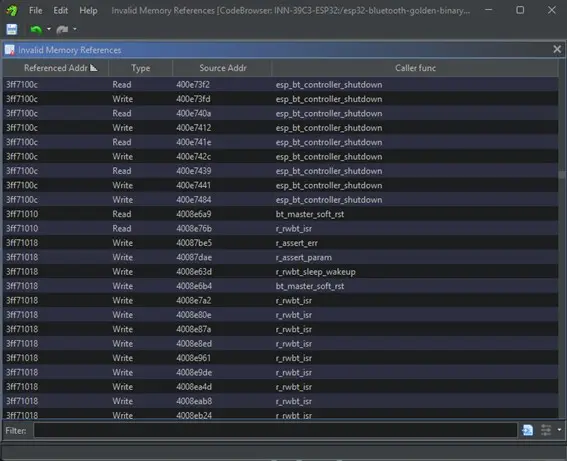

The code in Ghidra tries to access memory regions that are mapped to peripherals, but Ghidra does not allow us to list and enumerate the code that tries to access the unknown regions. For this purpose, the GhidraInvalidMemoryRefs plugin has been created.

The plugin simply lists where in the program there are pieces of code that try to access memory that has not yet been recognized and labeled. Using the resulting table, we can easily locate functions that have Bluetooth related names trying to access memory located at 0x3ff71000!

Figure 4. Invalid Memory References plugin listing Bluetooth related functions.

With the plugin, we were able to identify the region that is most related to Bluetooth code. Now we can explore all the functions that interact with this region of code and try to understand what each bit do and how the peripheral can be used.

The setup and the process

Mostly, what remains is to spend countless hours reading obscene amounts of code. The idea is from the existing information, trying to extract as much context as possible to understand how and why those memory locations are accessed at that place in the code.

Everything detail counts! Function names, debug information regarding source code file names and lines, assert strings that leak register names and even the usage of bitmasks allows us to understand how a register is split into smaller fields…

Reading is not always enough, and many tests had to be performed. For this, we developed many small firmware tests that were used to read and write values to registers and evaluate the impacts of the changes…

To facilitate the validation of some specific tests, we developed some custom ESP32 boards that had JTAG and SMA connectors to be able to real time debug the execution of the firmware while connecting the RF part of the ESP32 chip to other testing equipment such as SDRs and Bluetooth sniffers to perform measurements without external influences.

Figure 5. Custom ESP32 board connected to an ElectronicCats CatSniffer for testing.

Findings

After many hours of reversing and testing we started to document a surprising architecture that composes this Bluetooth peripheral.

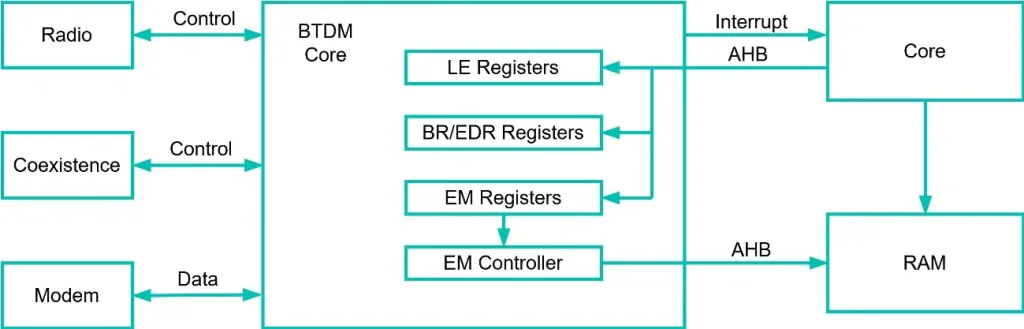

The BTDM (BlueTooth Dual Mode) peripheral oversees aiding the main processor with time sensitive operations that would occupy too much time of the main ESP32 processor if this was not present.

The peripheral relies on other peripherals such as a Radio, Modem or a Coexistence arbiter to send and receive RF information. The interfaces used to talk to those peripherals have not yet been reverse engineered, putting the effort on reverse engineering the main Bluetooth peripheral that is known to be possible to control by the user.

Also, the BTDM core communicates with the main ESP32 processing core via multiple interfaces that we have studied.

- Interrupts, that are signals that the BTDM Core can use to interrupt the main core, notifying the user that some Bluetooth event needs processing or some error has occurred.

- Registers that are a special portion of memory that triggers behaviours inside the BTDM core depending on their value. The main core can read or write to change general peripheral options such as enabling and disabling, error reporting, timing and clock settings, exchange memory configuration…

- Exchange Memory that is a portion of the general-purpose RAM that the BTDM and the main core share. This allows the BTDM Core to access general RAM in the same way as the main processor core can. The exchange memory will be used as the main Bluetooth information exchange mechanism.

Figure 6. Bluetooth peripheral architecture.

New updated SVD files have been generated to document BTDM records.

We have documented 40+ Bluetooth related registers and bitfields for 20+ registers in the Tarlogic’s GitHub repository. Hopefully, the documentation will land the original project at the Espressif Rust community, and the Espressif official repositories.

The exchange memory is extensively big and contains many linked tables. Each of this tables handles a part of the Bluetooth information exchange:

• What should the peripheral do at any moment? Scan, Advertise, Connect…

• Frequency and hop control for that slot…

• TX and RX buffers…

As a summary, in the ESP32, the exchange memory is mapped as follows:

| Address | Structure |

|---|---|

| 0x3ffb0000 | Exchange table |

| 0x3ffb0040 | Frequency table |

| 0x3ffb0090 | ?? |

| 0x3ffb0098 | BLE encryption |

| 0x3ffb00b8 | BLE Control Structures |

| 0x3ffb0480 | BLE Whitelist |

| 0x3ffb0510 | BLE Resolve Address List |

| 0x3ffb05ac | BLE TX Descriptors |

| 0x3ffb0934 | BLE RX Descriptors |

| 0x3ffb0994 | TX Control Buffers |

| 0x3ffb0b82 | TX Data Buffers |

| 0x3ffb15aa | RX Buffers |

| … | BR/EDR Stuff |

The relevant documentation regarding how this exchange memory is organized should not be put into an SVD file because it can be changed and mapped to any other region at any time and it does not describe hardware. For this reason, we have opted to document it in the form of header files in a separate repository.

An interesting detail on the device operation resides in understanding two difficulties of this design:

- Both the main core and the BTDM core can modify the exchange memory simultaneously. This would occur if a packet is received and the BTDM tries to write onto the exchange memory while the user was already writing the information for a packet transmission request. This can produce race conditions…

- Bluetooth operations are very time sensitive and should be run synchronized to a tight clock…

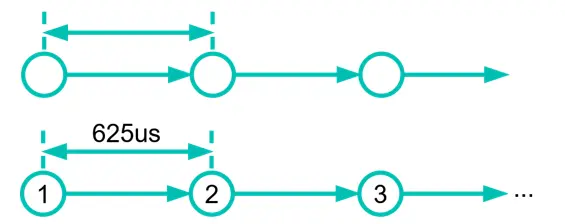

The ESP32 Bluetooth peripheral deals with this using a «pre-fetch» mechanism. The main exchange table defines 16 slots. The BTDM core will continuously iterate those 16 table entries and execute the operation of each slot synchronized to a 625us clock.

Figure 7. Slot execution graph.

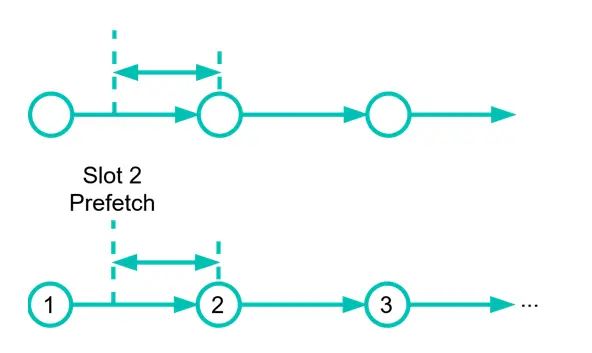

Instants before a slot is supposed to execute, the BTDM core is going to “pre-fetch” the slot data and verify if there is some pending operation to be executed. If that is the case, the BTDM core will wait for the clock signal and execute the action.

Figure 8. Slot information prefetch.

The user must be careful and must prepare all the information in the exchange memory in an empty slot and then wait for the prefetch interruption to signal in the exchange table that a slot can be processed. When everything is ready, the BTDM core will reach the corresponding slot and fetch the information for execution. At that moment, the user should not modify the existing information or otherwise, changes may not apply.

During the execution of the slot or after finishing the action, the BTDM Core will notify of updates or pending actions via interruptions to the main core.

What can be done?

Having a deep understanding of the operation of the BTDM core of the ESP32 allows us to perform all common Bluetooth operations directly using the hardware: Scan, Advertise, Connect…

This would enable anyone to write an open-source Bluetooth controller stack that can work on the ESP32.

On top of that, there is enough documentation to also perform some radio frequency test operations that allow for transmission and reception of Bluetooth Test packets. This may be useful for jamming a single channel in a continuous manner…

Also, understanding the hardware interface allows us to modify the existing Bluetooth controller software implementation to implement custom behaviours such as unexpected responses. This allows us to port existing proofs of concept for security checks and perform low level fuzzing.

An interesting project for security research would be to implement custom HCI packets to allow custom functionality out of our ESP32 device such as:

- Logging low level traffic to observe an analyse the underlying RF protocols that cannot be seen at HCI levels to study compliance with the standard.

- Perform per-channel scans, to obtain detailed information of devices that may allow us to identify and profile devices based on their behaviour despite using anonymizing mechanisms such as random MAC addresses.

- Send arbitrary BT low level traffic to test the resilience of other devices to unexpected packets using fuzzing techniques or to implemented known to work techniques for information extraction and exploitation.

- Follow and sniff connections whose establishment is captured, to monitor communication between devices without intervention in the data exchange.

- Continuous jamming of a single channel to prevent advertisements, connections or data exchanges in those channels, forcing the communication on the remaining channels. This is useful to improve the chances of getting hard to implement attacks to work in real scenarios.

- Limited sniff of third-party traffic. In Bluetooth, connected devices exchange packets that are preceded with a «synchronization word» that is unique to that connection. A mechanism is documented that allows, even if there are a certain number of errors in the bits of the «synchronization word», to capture possible malformed packets, so that data can be received using partially known «synchronization words».

What can’t be done?

In Bluetooth, connected devices exchange packets that are preceded with a “synchronization word” that is unique to that connection. Unfortunately, to date, we have not found any way of forcing the BTDM peripheral into a «full monitor mode» where we could receive packets without knowing the «synchronization word» for those packets.

It is also suspected that certain packets are processed internally so it is possible that not all Bluetooth packets may be available from this peripheral.

Future work

There is enough documentation to start writing an open-source controller stack that is easily modifiable and extensible although it would entangle a significant amount of work.

The existing implementation along with the documentation about the peripheral hardware, is enough to port most of the existing public Bluetooth low level tools, attacks and vulnerabilities to the ESP32.

Finally, it would be interesting to reverse engineer other parts of the ESP32 chips such as the modem or the radio frequency peripherals, to evaluate if the found limitations could be solved.

References:

- GhidraLinkerScript: https://github.com/antoniovazquezblanco/GhidraLinkerScript

- GhidraSVD: https://github.com/antoniovazquezblanco/GhidraSVD

- GhidraInvalidMemoryRefs: https://github.com/antoniovazquezblanco/GhidraInvalidMemoryRefs

- SVDs: https://github.com/TarlogicSecurity/esp-pacs

- Documentation: https://github.com/TarlogicSecurity/ESP32-Bluetooth-Reversing

- Slides: https://github.com/TarlogicSecurity/talks

- Talk video: https://media.ccc.de/v/39c3-liberating-bluetooth-on-the-esp32