Abusing automatic calendar processing for initial access and lateral movement

Table of Contents

Introduction

When we think of calendar invitations, we often picture attaching .ics files to emails manually. In practice, modern email clients process meeting requests automatically, adding them directly to our calendars without requiring the user to open a file attachment. To achieve this, clients rely on built-in automatic meeting processing capabilities that detect, interpret, and handle calendar events seamlessly.

To make this work, the iCalendar specification (RFC 5545) operates in tandem with the iTIP (RFC 5546) and iMIP (RFC 6047) protocols. Together, these standards define how calendar information is formatted and exchanged. Calendar events are transmitted as MIME parts using the text/calendar content type, allowing structured event data to be embedded directly within standard email messages. This ensures that different systems can reliably interoperate across scheduling, modification, and cancellation workflows.

The METHOD property in the iCalendar data dictates how the receiving client should interpret the message:

REQUEST: indicates the sender is proposing a new event or meeting invitation, prompting the client to display RSVP options to the recipient.

CANCEL: used when an organizer withdraws a previously scheduled event. When a mail client receives a cancellation message that references an existing event, it maps the update to the calendar entry and removes it or marks it as canceled.

--===============8312836043581261466== Content-Type: text/calendar; method=REQUEST; charset="utf-8" Content-Transfer-Encoding: 7bit BEGIN:VCALENDAR [...] END:VCALENDAR --===============8312836043581261466==--

Throughout this post, we explore how the handling of emails that make use of these protocols opens an opportunity to conduct creative social engineering scenarios. To demonstrate this, we will use Tangled, an open-source social engineering platform developed by our team that weaponizes the features that will be discussed during this blog post.

Overview of a VCALENDAR object

In iCalendar messages, the VCALENDAR object acts as the top-level container. It encapsulates one or more components, including VEVENT, which represents a single calendar entry such as a meeting, appointment, or reminder. Each VEVENT is enclosed between BEGIN:VEVENT and END:VEVENT and contains a set of required and optional properties that describe every aspect of the event.

While email clients may require or interpret fields differently, some properties are mandatory to function properly and standard across most events:

Key attributes of a VEVENT

- UID (Unique Identifier): the most critical field for logic. It identifies the event across updates, reschedules, cancellations, or transfers between systems. Mail clients use it to match incoming REQUEST or CANCEL messages to existing calendar entries.

- DTSTAMP: a timestamp indicating when the event object was created by the organizer’s system.

- DTSTART / DTEND: the start and end time/date of the event. Values may be floating, UTC, or tied to a VTIMEZONE definition within the VCALENDAR.

- ORGANIZER: it identifies the person responsible for creating or managing the event.

- ATTENDEE(S): specifies the participants invited to the event.

- SUMMARY: the title of the event. It corresponds with the visible name of the meeting in many email clients.

- DESCRIPTION: the body text of the event or meeting notes.

- LOCATION: the venue, room, or virtual meeting URL of the event.

- SEQUENCE: a positive integer indicating the version of the event. When an organizer sends updates, the SEQUENCE increments so clients know it replaces a prior version.

- STATUS: TENTATIVE, CONFIRMED, or CANCELLED.

- CLASS: defines access restrictions (PUBLIC, PRIVATE, or CONFIDENTIAL).

- RRULE: recurrence rules for repeating meetings (optional).

BEGIN:VCALENDAR METHOD:REQUEST PRODID:Microsoft Exchange Server 2010 VERSION:2.0 BEGIN:VTIMEZONE TZID:W. Europe Standard Time BEGIN:STANDARD DTSTART:16010101T030000 TZOFFSETFROM:+0200 TZOFFSETTO:+0100 RRULE:FREQ=YEARLY;INTERVAL=1;BYDAY=-1SU;BYMONTH=10 END:STANDARD BEGIN:DAYLIGHT DTSTART:16010101T020000 TZOFFSETFROM:+0100 TZOFFSETTO:+0200 RRULE:FREQ=YEARLY;INTERVAL=1;BYDAY=-1SU;BYMONTH=3 END:DAYLIGHT END:VTIMEZONE BEGIN:VEVENT UID:74C5FE197DF6036AC2078CE1A30 ORGANIZER;CN=Inés Martín:mailto:ines.martin@tangledsec.com ATTENDEE;ROLE=REQ-PARTICIPANT;PARTSTAT=NEEDS-ACTION;RSVP=TRUE;CN=Marcos Díaz:mailto:marcos.diaz@tangledsec.com DESCRIPTION;LANGUAGE=en-US:Follow up meeting SUMMARY;LANGUAGE=en-US:End of Week Wrap-Up DTSTART;TZID=W. Europe Standard Time:20251205T140000 DTEND;TZID=W. Europe Standard Time:20251205T143000 CLASS:PUBLIC PRIORITY:5 DTSTAMP:20251205T120632Z TRANSP:OPAQUE STATUS:CONFIRMED SEQUENCE:0 LOCATION;LANGUAGE=en-US:Online BEGIN:VALARM DESCRIPTION:REMINDER TRIGGER;RELATED=START:-PT15M ACTION:DISPLAY END:VALARM END:VEVENT END:VCALENDAR

In addition to key standards, major clients like Microsoft Outlook and Gmail implement proprietary fields and custom properties. Not only that, but each email client decides how the rendering is done for each of the properties.

Abusing automatic event processing in Outlook

Event Invitations

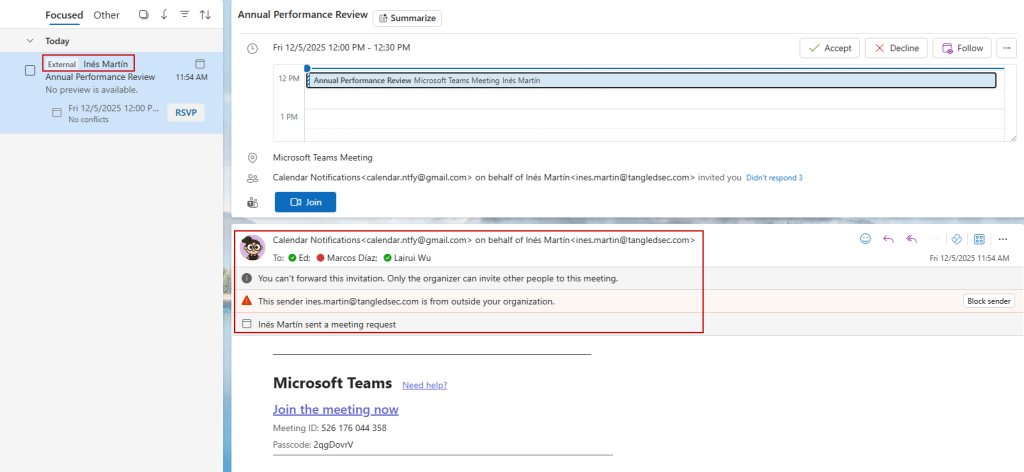

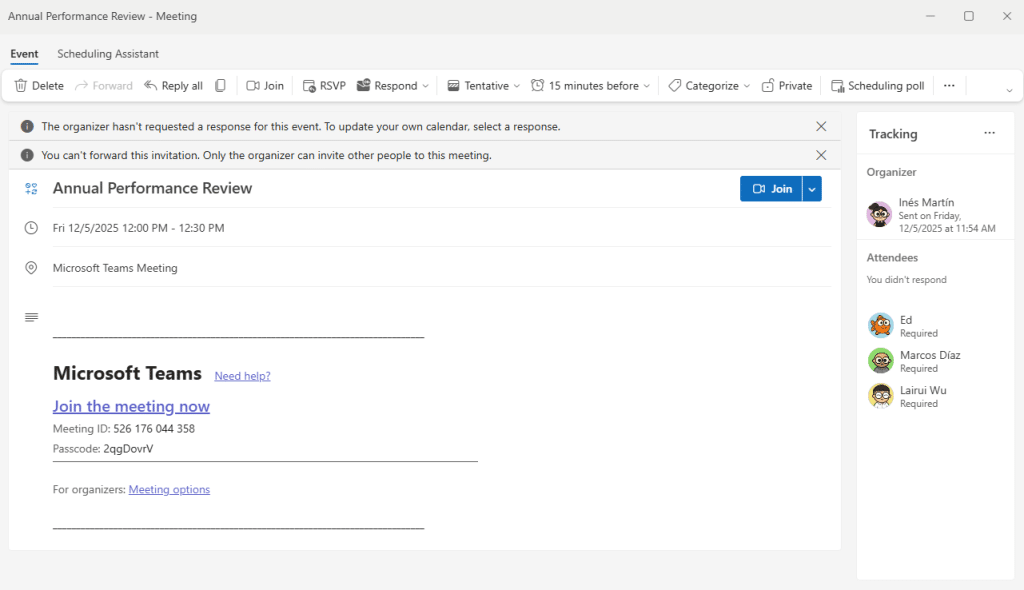

There is a feature enabled by default in Microsoft Outlook that automatically processes meeting requests, allowing the integration between Outlook and Microsoft Teams event workflows. By replicating the structure of these legitimate calendar events, an attacker can send a compliant RFC email that gets automatically processed and added to the victim’s Outlook calendar, regardless of whether they accept the meeting. Furthermore, the event will persist in the user’s calendar even if the originating email is deleted.

These events are rendered without proper validation, which can be abused to spoof the information contained inside the VCALENDAR block, including the organizer, attendees and location.

Not only that, it seems that Outlook relies on the organizer field to render the email sender in the UI, allowing us to effectively spoof the email sender’s identity. In addition, Outlook provides vendor-specific properties that allow us to manipulate other UI properties, such as email tag categories, meeting attached files or even priority flags, making these malicious meetings look highly realistic.

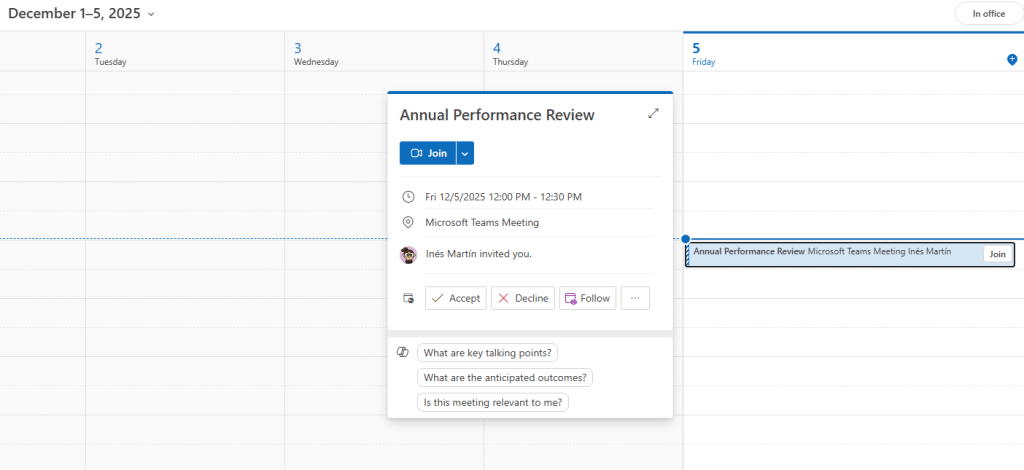

The spoofing becomes even more convincing if the organizer belongs to the same tenant as the recipient, as Outlook will resolve the user against the directory, displaying their name, profile picture, status, and recent shared activity when hovering over the invite organizer. The same applies to meeting attendees. In the inbox mail list on the left, the name and picture of the spoofed organizer (might depend on the Outlook version) will also appear. Outlook also attempts to automatically link accounts to LinkedIn, so if an organizer or attendee that is registered on LinkedIn with that email address is specified, it will associate their external profile details.

Note that an “on behalf of” tag next to the original sender is added, as well as a warning banner stating that the organizer mail is from outside the organization (clearly not the intended behavior).

By default, when a user interacts with the meeting (accept/decline), the organizer listed in the event receives an RSVP email. If we are spoofing a legitimate user, they would suddenly receive an acceptance mail… for a meeting they never created. That would be weird, right? To maintain stealth, we can add specific attributes to the VCALENDAR block (such as the X-MICROSOFT-ISRESPONSEREQUESTED header) to suppress these automated response messages.

Once processed, the event appears in the calendar looking completely legitimate.

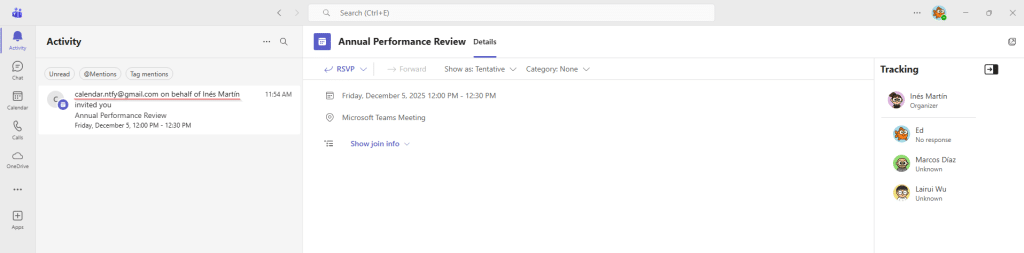

If we have Microsoft Teams connected, we will also get a notification about the event, just like it would regularly happen with a legitimate meeting. On the left panel the original sender will appear, however, the calendar section looks similar to the one in Outlook.

Finally, let’s examine some of Microsoft’s proprietary features. Since these events are widely used for conferencing, one might wonder how Microsoft Teams processes meeting URLs in events. To do that, it adds vendor-specific headers like X-MICROSOFT-SKYPETEAMSMEETINGURL. By introducing these headers manually, we can achieve the same native rendering, resulting in meeting events that redirect users to arbitrary URLs that are not necessarily from Microsoft Teams.

Additionally, the VCALENDAR specification allows specifying custom meeting notifications (VALARMs), enabling us to trigger pop-up alarms some minutes before the meeting to remind users to join the meeting.

Event reschedules and cancellations

As established before, an event is tied to a unique identifier (UID). If we possess this identifier, the event can be rescheduled or cancelled. To determine the last version of an event, the protocol uses the SEQUENCE attribute. This is an integer that typically starts at 0 and increments with every update. Therefore, to make a modification or cancellation, we simply need to transmit an email with an event containing the same UID and a SEQUENCE value higher than the previous version.

Rescheduling allows modifying some meeting details such as the attendee list, date, time, or location. Once an email is received referring to the same event UID, the emails will be stacked into a conversation. Cancellations will also remove automatically the event from the calendar and send the originating invitation email to the trash folder (which is surprisingly nice opsec for Red Teams). In both cases, the corresponding update/cancellation notification is also received and processed in Microsoft Teams.

Bonus: spoofed Teams meetings

After taking a deep look into the format of Microsoft Teams meetings, I realized they could be created arbitrarily, without the need to register them through any kind of API call.

A meeting URL has the following format:

https://teams.microsoft.com/l/meetup-join/19%3ameeting_{b64(<opaque>)}@thread.v2/0?context={enc({“Tid”: <TID>, “Oid”:<OID>})}

This can be broken down into three parameters:

- Opaque: appears to be the meeting UUID.

- TID (tenant id): represents the target tenant’s UUID.

- OID (object id): corresponds to the organizer’s object Entra ID identifier.

My initial thought was to question whether these parameters were actually validated. After inserting random organizer and opaque values alongside my actual tenant ID, I was able to successfully access a Teams meeting. This means that arbitrary Teams meetings can be created in a specified target tenant, with the only limitation that, as they are not generated by the corresponding API generation flow, there is no chat room associated with the meetings. Still, all other features (voice, screen sharing…) seem to work perfectly.

In short:

Random organizer ID + Target tenant ID + Random opaque = Profit

The meeting is “hosted” on the specified tenant ID. This means that if a user from an external tenant tries to join the meeting, they will require approval from one of the attendees. This feature is interesting, as it can be weaponized in various ways, ranging from meetings where a Red Team operator issues malicious instructions, to meetings that serve purely as decoys… use your creativity!

Putting it all together: demo time

With all these concepts in mind, it’s time for a demo. A malicious meeting will be sent from a personal mail account spoofing ines.martin@tangledsec.com. When the user (Ed) tries to join the meeting, he will be redirected to a malicious website that replicates Microsoft Teams, asking for his corporate credentials to join the meeting. After capturing his session details, he will be redirected to a spoofed Microsoft Teams meeting, where he will wait until the other participants join the meeting. However, after a while, he will get an email cancelling the meeting.

Silently hijacking existing meetings

Another interesting use case is internal phishing. In the supposed scenario where we have compromised a user’s Microsoft account, we could access their inbox and inspect their calendar for upcoming meetings. After finding a suitable one, we could download the corresponding meeting invitation email to gather the necessary information and send a malicious update to the rest of the participants, replacing key details of the meeting to execute a targeted social engineering attack.

One of the highlights of this technique is that, when a meeting is accepted, the entire conversation thread is automatically sent to the trash folder. As a result, the rescheduling email will appear as just another stacked message hidden in the trash, making it almost unnoticeable to the user.

The following video demonstrates how this can be weaponized, effectively modifying an existing event’s details to lure the target into entering his credentials. Once the session information is captured, the victim is redirected to the original Microsoft Teams meeting, allowing him to join his teammates without raising any suspicion.

Abusing automatic event processing in Gmail

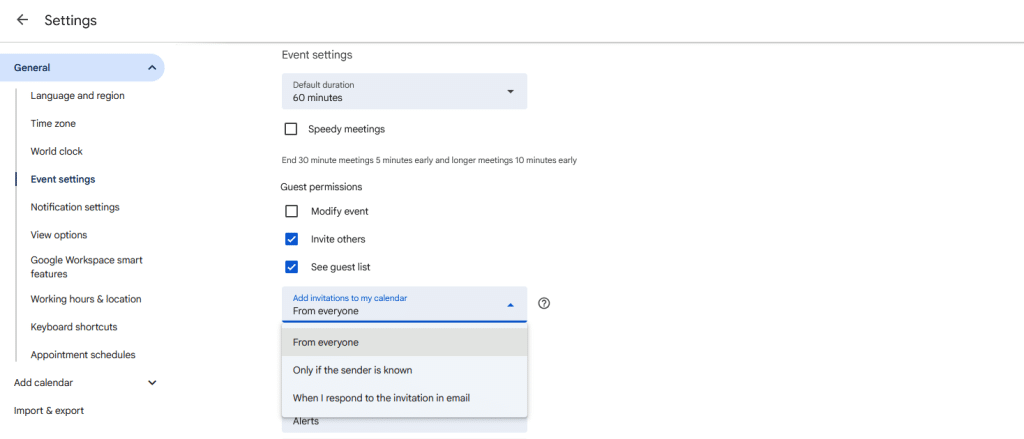

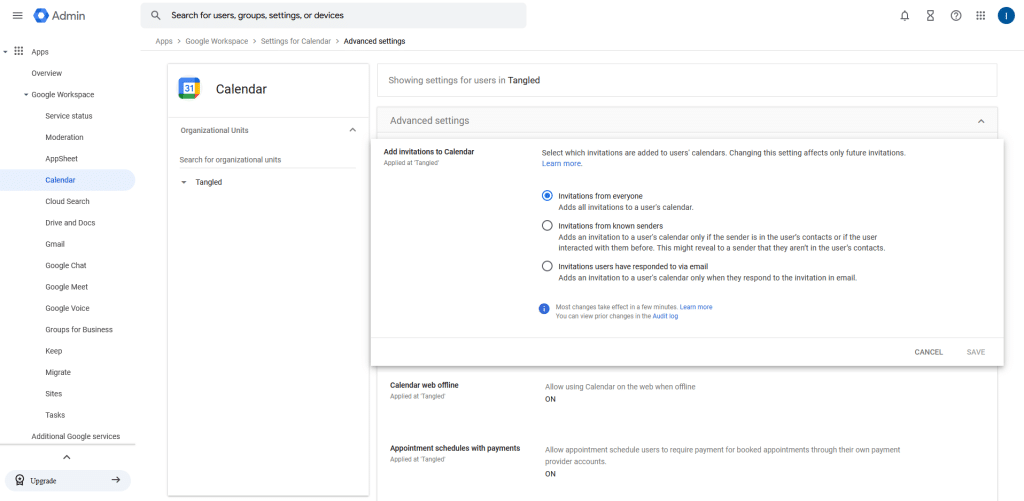

Gmail also automatically processes meeting requests. In Google Workspace organizations, this policy is configured via the admin console for all directory members. However, individual users can subsequently modify this setting manually.

There are three possible options: add invitations to my calendar from everyone, only if the sender is known, or only when responding to the invitation in email.

The default setting value allows invitations from everyone to be added automatically. However, if it were to be restricted, the most common choice would be to set the “Only if the sender is known” setting. This classifies “known users” as anyone you have interacted with, primarily through email conversations or replies. However, I noticed that when receiving an invitation, if the user clicks “Yes,” “No,” or “Maybe,” the sender will be marked as “known.” This automatically adds the current event —and all future ones— to the calendar. I guess this small interaction is enough to make a social engineering attack viable.

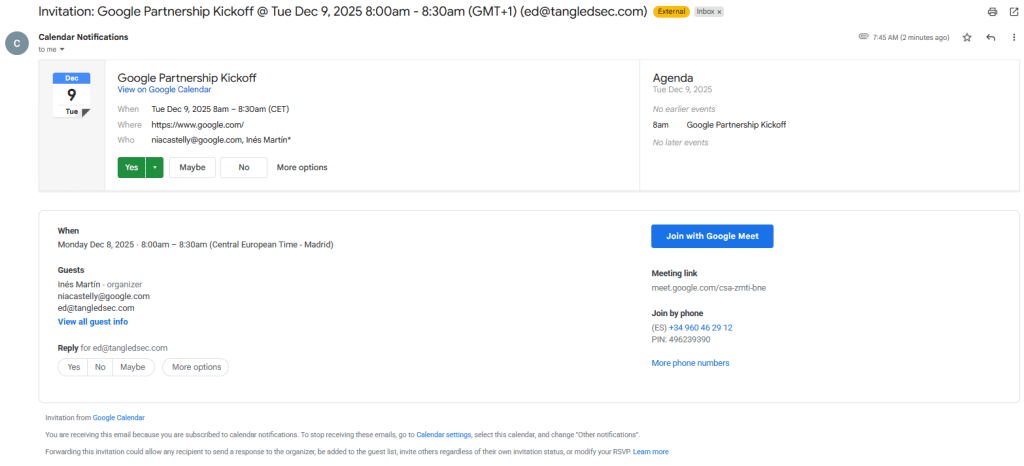

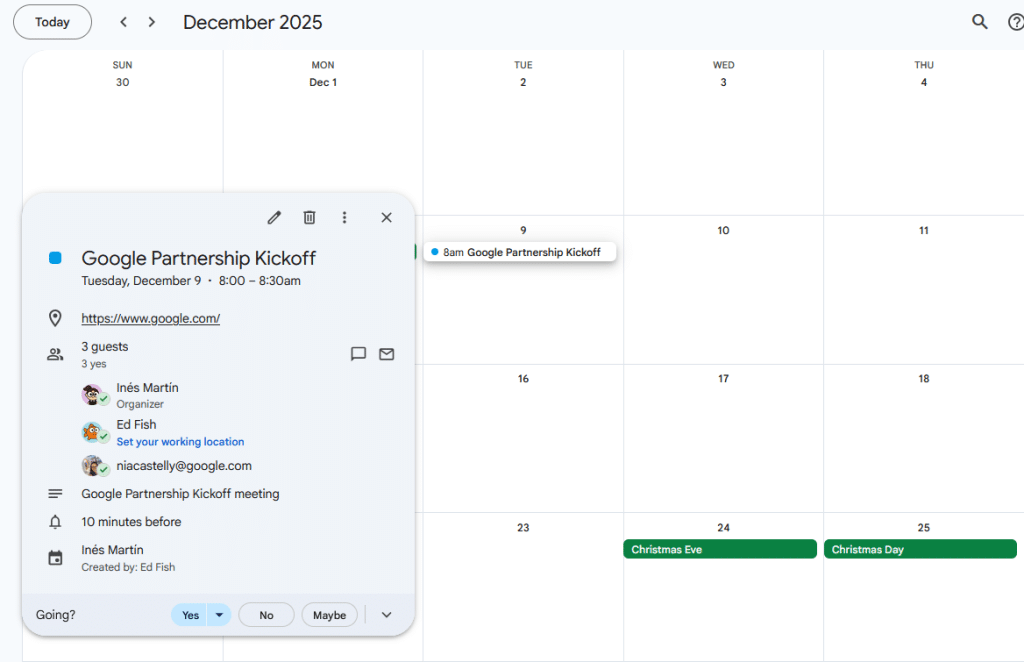

Anyways, the automatic event processing feature in Gmail presents a similar abuse vector to Outlook, although it has some differences. It is also possible to impersonate the event meeting organizer and attendees. However, profile pictures will only appear if the recipient has permission to view that profile information, depending on the organization’s configuration (though it is commonly enabled). Consequently, the spoofed organizer and attendees’ names and profile photos (if available) will be displayed in the target user’s inbox if they use Google Workspace. In this case, these images may even be visible from outside the organization.

Another interesting detail is that it is possible to manipulate the event status so that it appears already accepted by the organizer, attendees, and even the recipient themselves. By combining these details with the appearance of legitimate Google Calendar mail invitations, it is possible to craft highly realistic phishing invitations.

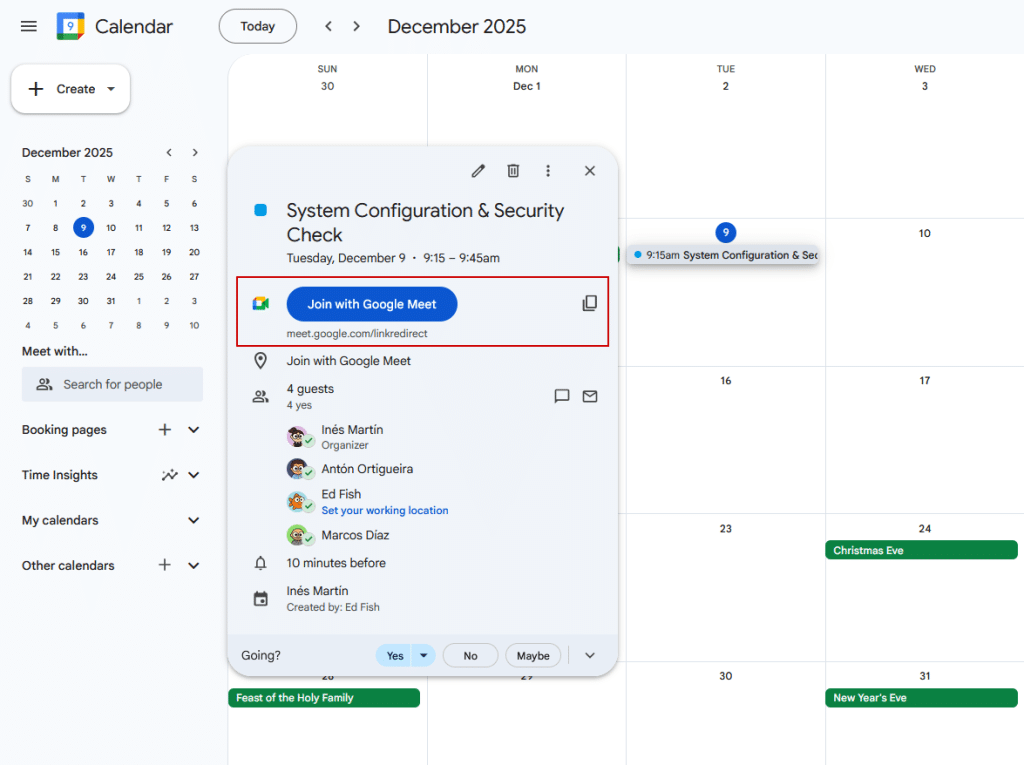

Notifications will also be triggered to announce that a meeting will start shortly. On the other hand, for conferencing, Google also uses its own proprietary headers to insert meeting information. However, this time, the meeting links are sanitized, so adding an arbitrary URL doesn’t render the “Join with Google Meet” button in a calendar event. Instead, the Location field can be used, as it gets rendered as the meeting place if it contains a valid URL.

Bonus: malicious “Join with Google Meet”

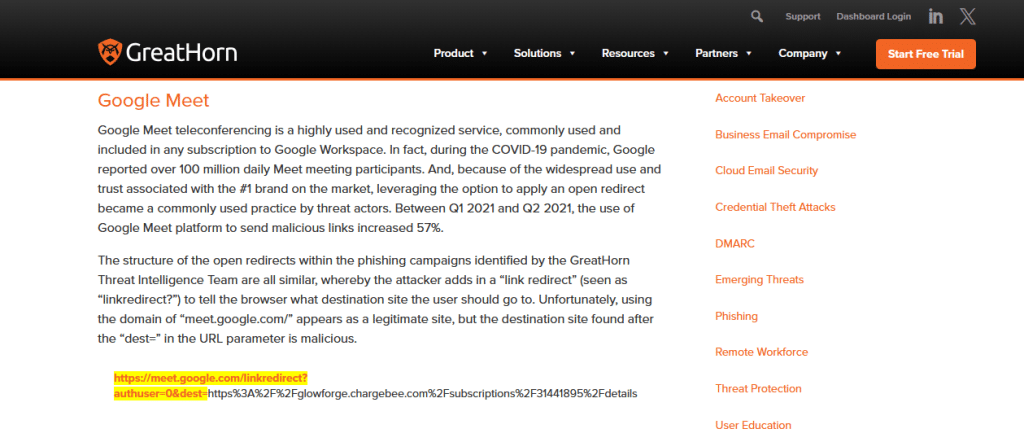

We previously discussed Google sanitizing URLs inserted into the X-GOOGLE-CONFERENCE header value. But how is this validation actually implemented? Typically, a Google Meet video call URL follows the format https://meet.google.com/xxx-xxxx-xxx. After some testing it seems that the client only whitelists links belonging to the meet.google.com subdomain. In theory, this should prevent an attacker from inserting an arbitrary malicious URL… right?

Well, it would, unless the URL allowed other paths deviating from the standard format and Google Meet’s domain itself had an Open Redirect vulnerability. A brief investigation quickly revealed that meet.google.com does, in fact, contain a known Open Redirect vulnerability.

It appears this Open Redirect vulnerability was abused around 2021 and was eventually “fixed”. However, the remediation was partial: the solution was to route traffic through Google’s own redirect system. This mechanism displays an intermediate warning banner that requires explicit user interaction to follow the target link. For example:

https://meet.google.com/linkredirect?dest=https://www.tarlogic.com/es/blackarrow/

This banner definitely does not look phishing-friendly. However, after further testing, my teammate Marcos Díaz (@Calvaruga) realized that if the URL parameter pointed to certain trusted Google domains, it would redirect directly without displaying the warning banner.

So… would using Google Meet’s open redirect to trigger Google’s redirect system to redirect to a Google’s trusted domain open redirect into our malicious URL work???

As a quick PoC, we leveraged a known open redirect vulnerability in Google Docs. Although this specific link is valid for only one hour, it was enough to validate the attack vector. As a result, the “Join with Google Meet” button rendered successfully, redirecting the user to an arbitrary URL. We later discovered other Open Redirect vulnerabilities in the wild that do not expire, which could be abused in real-world social engineering campaigns.

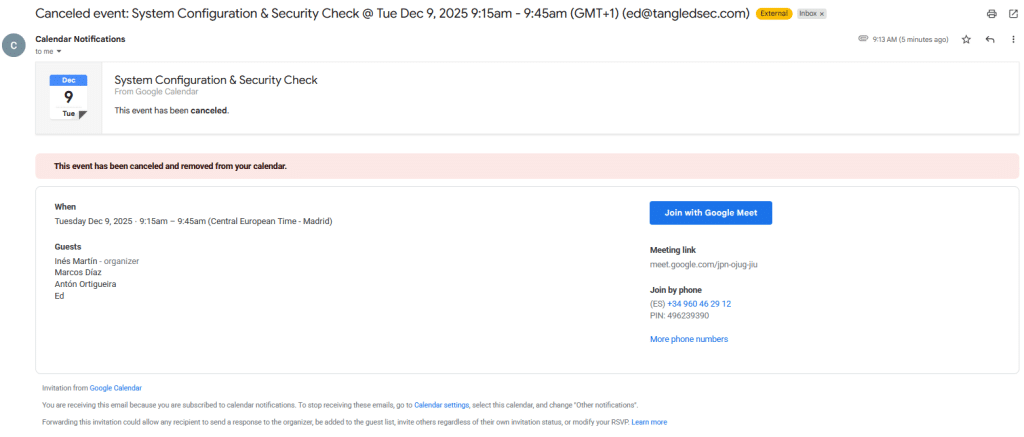

Event reschedules and cancellations

Again, if we possess an event identifier, a meeting can be rescheduled or cancelled.

If the meeting is cancelled, the event will be automatically removed from the calendar. However, in Gmail, cancellation emails are treated as standard messages and therefore not automatically organized into threads or moved to the trash folder.

On the other hand, Google does not appear to parse external events that utilize its native UID format (<id>@google.com). This restriction prevents external invitations from overriding existing meetings, effectively acting as a safeguard against internal phishing attempts.

Putting it all together: demo time

Again, it’s time for a demo. A malicious meeting will be sent from a personal mail account spoofing ines.martin@tangledsec.com. When the user (Ed) tries to join the meeting, he will be redirected to a malicious website that replicates Google Meet and will require to download some kind of malware. After completing the required steps, he will access a fake meeting website, where he will wait for the other participants to join the meeting. However, after a while, he will get an email cancelling the meeting.

Mitigations

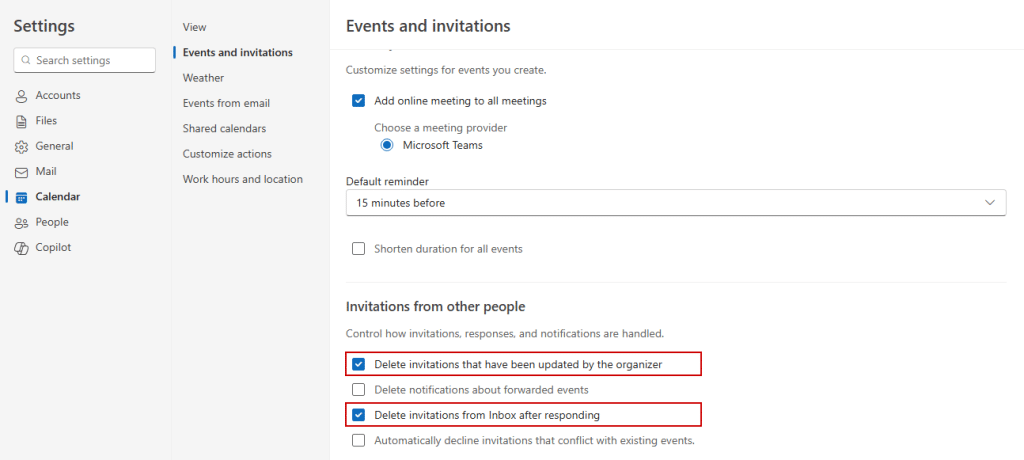

For Outlook: consider disabling the automatic processing of meeting requests and responses. This setting is a bit tricky, as many Microsoft forums mention disabling the “Automatically process meeting requests and responses to meeting requests and polls”1 setting in Outlook classic (this setting doesn’t appear in the new Outlook), but I personally wasn’t able to make it work.

In other discussions, the Set-CalendarProcessing PowerShell cmdlet is mentioned as a solution to perform a bulk update across all tenant mailboxes by applying the AutomaticProcessing None parameter, and effectively disabling automatic calendar handling, such as auto-accepting or tentatively adding meeting invites2. However, this cmdlet is only effective on resource mailboxes.

Regarding overriding the details of existing meetings, I tried unchecking the following settings in the modern Outlook client, with the goal of preventing these emails from being sent directly to the Deleted items folder, giving users a chance to notice the malicious update email. Unfortunately, despite legitimate invitation mails remaining in the inbox, the malicious event updates still ended in the trash folder. This didn’t prove to be an effective solution, at least in my current setup.

Consequently, there seems to be no reliable client-side method to disable this behavior in Outlook at the moment. However, Exchange Online mail flow rules can be configured to manage calendar invites and set rules to detect and block meeting requests from external senders3.

Additionally, Microsoft recently launched enhanced remediation support for the calendar4, which includes a Hard Delete option that allows mitigating active phishing campaigns by removing the associated calendar entries for any meeting invite email.

For Google: consider changing Google Calendar settings to add invitations automatically only when an email notification is responded to. This can be done individually or globally:

- Individually: Select General > Event settings > Add invitations to my calendar: “When I respond to the invitation in email”. 5

- Globally: To set the setting for all users in the directory, navigate to the Google Admin console > Apps > Calendar > Advanced settings and click “Add invitations to Calendar” to set the desired option.

Disabling completely the automatic meeting processing might not be feasible in big organizations where meetings are frequent or third-party scheduling services are used.

So, in both cases, the best approach might be implementing email detection rules to quarantine or block this kind of emails based on the organization’s needs, for example, externally sourced emails containing embedded ICS files where the organizer is different from the sender and the sender is not trusted.

Additionally, it is recommended to configure external warning banners. This visual cue is crucial for distinguishing between legitimate internal communications and external spoofing attempts.

Conclusions

While automatic calendar invite features were originally conceived to streamline productivity, seamlessly bridging the gap between emails and scheduled events, they have inadvertently introduced a significant attack surface. The absence of robust validation mechanisms, likely exacerbated by the complexities of third-party calendar integration, has resulted in unexpected rendering behaviors.

This research illustrates how sophisticated attackers can weaponize this feature and bypass standard protections to carry out highly realistic social engineering scenarios, further underscoring that productivity-oriented features can quietly broaden the attack surface. Treating calendar events as active, potentially adversarial content rather than passive metadata is essential for building resilient, modern defensive strategies.

- https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/change-how-outlook-processes-read-receipts-and-meeting-responses-3e18ef46-57c0-4e49-ad89-b44ae75596ed, https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/answers/questions/4617569/stop-invites-automatically-adding-onto-the-calenda ↩︎

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/answers/questions/5558001/how-to-prevent-calendar-invites-from-external-sour ↩︎

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/exchange/security-and-compliance/mail-flow-rules/use-rules-to-add-meetings ↩︎

- https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/blog/microsoftdefenderforoffice365blog/strengthening-calendar-security-through-enhanced-remediation/4456876 ↩︎

- https://support.google.com/calendar/answer/13159188?hl=en# ↩︎